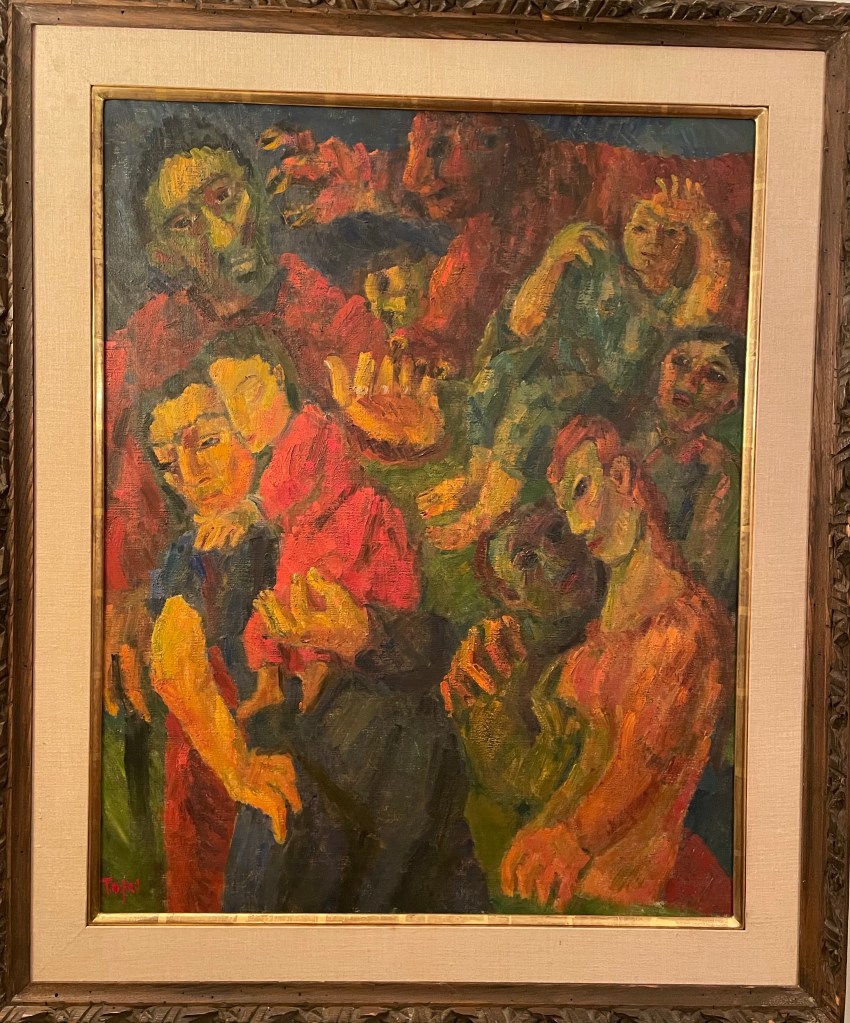

Collection of Pat and Ray Hickman.

LIS When I set out to write this, my goal was to reflect upon how Jennings Tofel influenced my life. Instead, it seems to be more stream of consciousness about my mother’s influence with a few sprinkles of other family members and then Jennings Tofel—kinda where you’d put the cherry. In fact, Shirley and Jennings inspired my curiosity about and passion for art. So, we’ll see where this ends up and how you and I feel about it.

I cannot write about Jennings Tofel without writing about my mom, Shirley Tofel Ernest. Her influence so much informed who I am today. It’s generally accepted most of us turn out to be a combination of the environment we grew up in plus our genetic pre-disposition. Growing up close to Manhattan, and also the ocean, provided plenty of opportunities for nurturing, and Shirley was the queen of nurture. She dragged Pat and me to libraries, museums, plays, musicals, galleries, high teas, and French restaurants. We did picnics and fed ducks, looked up at the trees and the sky–counted clouds, counted stars, counted waves. She would recite poems like “Trees” by Rudyard Kipling, “the Swing” by Robert Louis Stevenson, Emily Dickinson’s “I’m Nobody.” We wrote haikus and limericks.

Shirley owned her share of art posters and as many original paintings as she could muster, including two by Jennings Tofel. I discovered a pile of Shirley’s poems after she died. She befriended people like Uncle Jennings and “Gay Cousin Larry,” because they were “others” and she was determined we would understand, respect and accept diversity. She devoured books. And she read the New York Times every day. She cooked, cleaned, taught 5th grade in a public school in Rockville Centre, NY and was never too tired or angry to give and receive hugs. After our dad passed away, she got progressively mean and grumpy but that’s fodder for another blog.

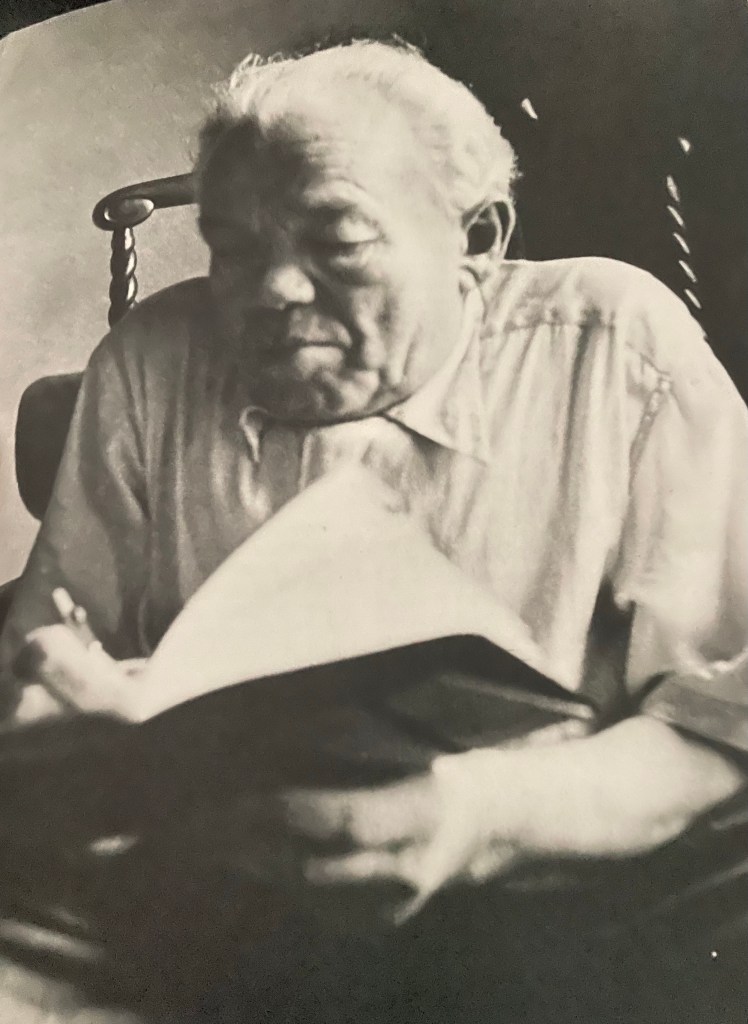

Uncle Jennings was her uncle. He was Shirley’s dad’s brother. I think I may have heard or read Papa George and Uncle Jennings were half-brothers. Nana Eva told us Uncle Jennings’ disabilities resulted from being pushed off a roof during the Nazi pogroms in Eastern Europe. Research seems to indicate he accidently fell off the roof when he was a kid and his numerous broken bones were never set properly. The bottom line is George and Jennings shared genes. Gentle George married Eva the Pepper Pot and owned an Army/Navy store in Poughkeepsie, called Terry’s. He was a lousy businessman. He loved to read and smoke cheap cigars. Jennings married Pearl and became an artist and writer who lived in New York and Paris. He had patrons.

In the early 20th Century, if you were an artist and you lived in New York City (or Paris) you were a Bohemian. I was told bohemian meant “ne’er-do-well,” which was one of Nana Eva’s favorite expressions, along with “I’ll been there in two shakes of a lamb’s tail” and “Girls! Keep your pants on.” I could never figure out either of these. I think the pants she referred to were underpants. Recently I learned the “lamb’s tail” expression derived from the Manhattan Project? Eva definitely was the bomb.

Anyway, Shirley argued (to no avail) that being a bit of a bohemian is a good thing. It meant you are unique and unconventional. And creative. Right?

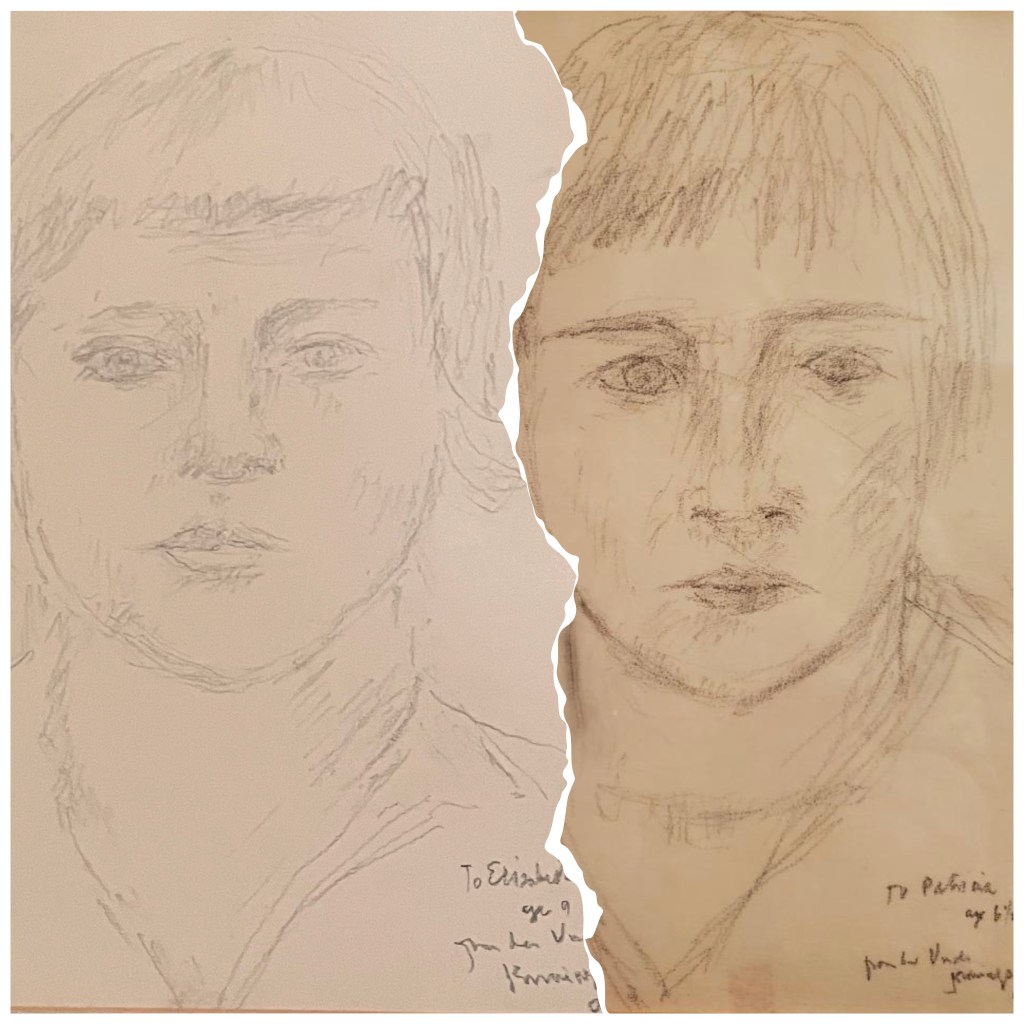

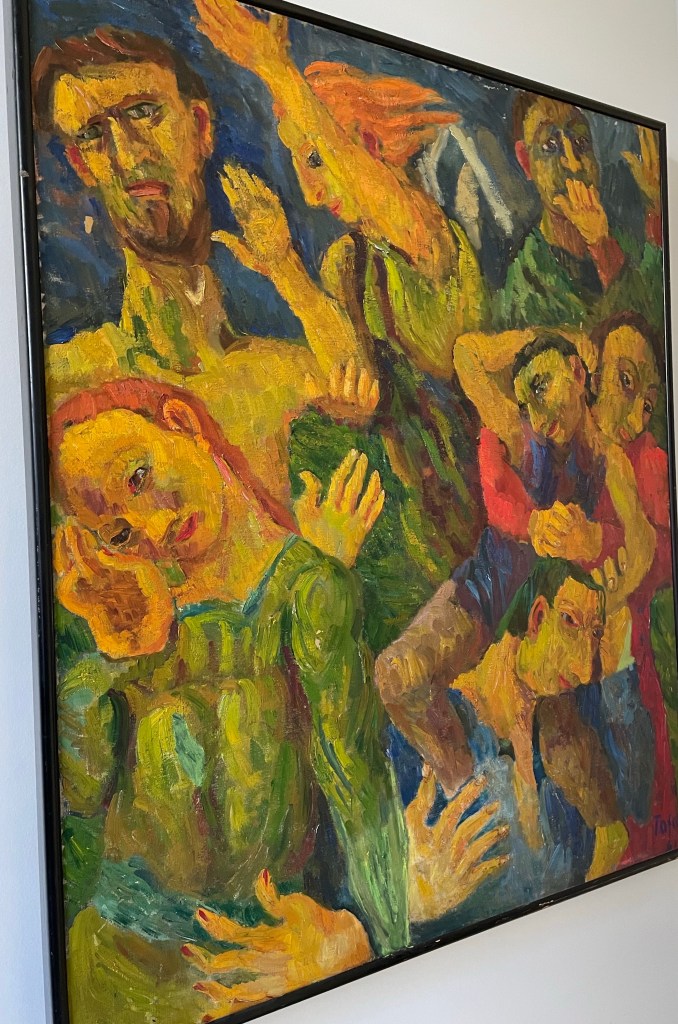

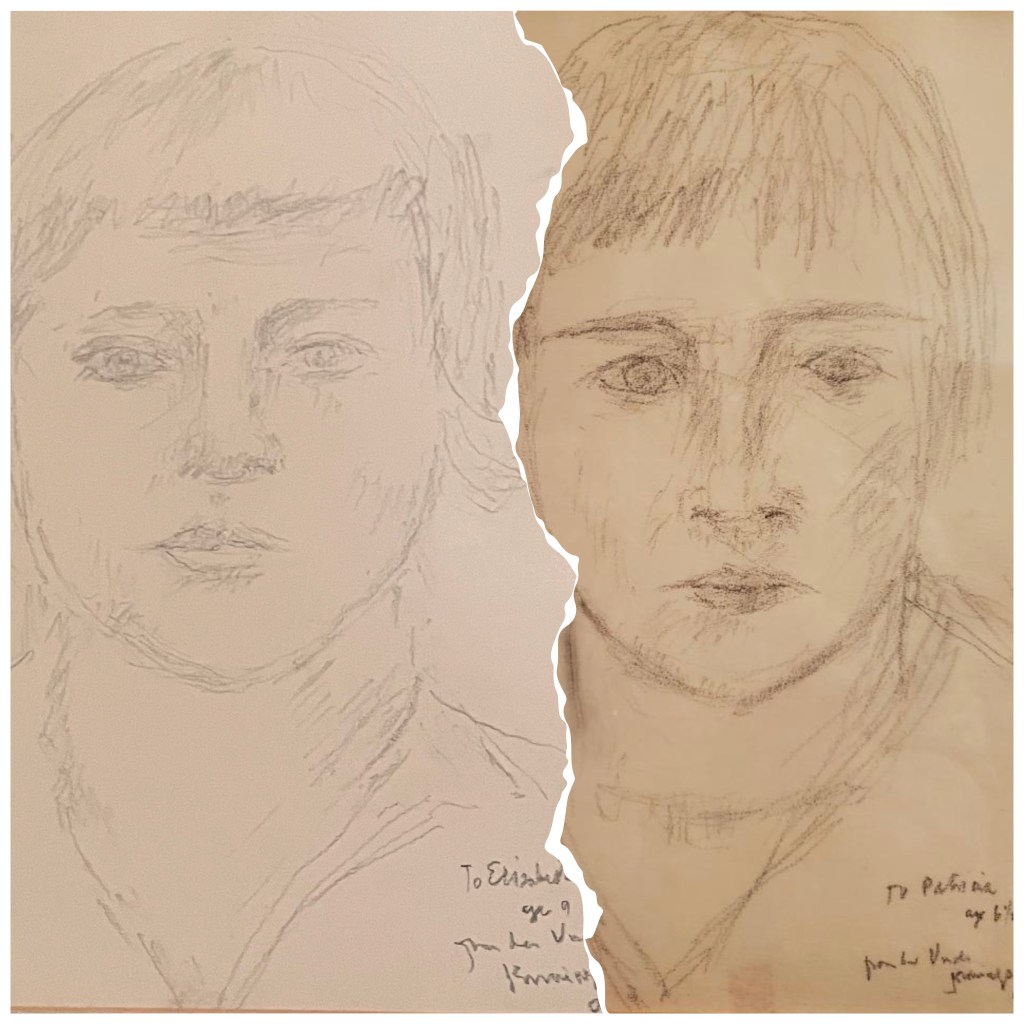

Whatever the rest of the family thought about Jennings, to me he was a hunched over disfigured little man who created strange paintings with mystical, colorful, bizarre, twisted, entangled human and animal figures. Expressionist. Grotesque. I was terrified. I was fascinated. In 1958, when Shirley asked him to sketch Pat and me, my nine-year-old self figured we would come out green and orange and looking like half girls/half monkeys. I refused to smile. Neither would Pat. I suspect Uncle Jennings saw in Pat and me two scaredy cat brats. Methinks we both came out looking like kids from the Village of the Damned.

Truth is nothing can compete with being sketched into art by a family member who wrote poetry and essays and who made paintings for a living. The session with our semi-famous Great Uncle had a lasting effect on our lives. Shirley made it all happen. Uncle Jennings passed away in 1959.

I think Tofel’s paintings depict a subjective reality of himself. In “Essays in Intimacy” from the 1927 The American Caravan, he writes, “there is no distance between me and the things I behold.”

What was The American Caravan you ask? I had to weave it into this blog. It’s a name dropping thing. So get ready! I bought a copy of the book for seven bucks from an Amazon bookseller and trembled when I first touched it. The editors of this 843 page 1927 anthology hoped the book would affirm the health of young American literature. It contained short pieces written by the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Paul Green, J. Brooks Atkinson, Witter Bynner, Morley Callaghan, Hart Crane, Babette Deutsch, John Dos Passos, Eugene O’Neil, Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams and JENNINGS TOFEL. The authors agreed they would share equally in the profits and had no expectations there would be any. Definitely Commies. Laugh out loud. I am dumbstruck by this book. It will take me months to finish reading it but I will.

I figure I have inherited a smattering of genetic particles from Uncle Jennings by way of Papa George and Shirley. I know this because there’s a bohemian inside me forever trying to push me out of her way. And I am wild about art. I am not a maker of visual art like Uncle Jennings was, but I and art live with each other. And I try my best to make art with my words. I write poetry. Most of my poems and the artworks who live with me are curious. My favorite people are “others.” In fact, I want them to rub off on me.

So. After nearly 73 years, what have I gleaned from these art nurturings and inspirations?

Collection of Lis and Mike Kalogris.

1. It’s never too late to start making or collecting art. There are affordable and wonderful art works to be found at art fairs, at open studios and at art school student exhibitions. Online art sites are overflowing with worthy and inexpensive art works. I googled “Jennings Tofel” and discovered many of his works are available to buy online. He was exceedingly prolific. Remember. Looking is free.

2. Find the bohemian or whatever else is bottled up inside you and set it free.

3. Never be intimidated by artists, crafters, artisans, collectors, gallerists.

4. There’s no rule that says you must love the artist if you love the work.

5. Artists need to earn a living. Where are the patrons?

6. And speaking of living, methinks art is high on the list of living essentials. By living essentials I mean things like breathing, eating, loving, smiling, dancing.

7. Art and craft are virtually the same thing. This is my opinion. Check out the ACC craft shows, the Philadelphia Museum of Art Craft Show, Long’s Park Art Festival and others all over the country and beyond. Bring your kids and grandkids. You don’t have to buy anything except an admission ticket.

8. Art is not really décor. Really. Art is not décor. Fire a decorator who is all about matching a painting to a sofa or vice versa. Only buy art you love even if you have no idea where it might land. You will find a spot for it. Live with art. Move it. Take note of the light and shadows playing on your artworks. Find art for your garden or terrace. My brilliant friend Eileen introduced me to the notion of a residential sculpture garden. After that, there were no holds barred for me. Cate, my Garden Angel, hacked, planted, arranged, trimmed all my crazy ideas and hers into what we called, the End of the Beginning Garden.

9. Write some words every day. Every single day. Bathe. Brush your teeth. Breathe. Write some words. Sketching, sculpting, weaving, quilting, painting, etching, photographing, composing, etc. also work if words won’t.

10. Photography is art!

PS “No one is alone, truly, no one is alone.” Stephen Sondheim 1930-2021

PPS Pat (Norg) is turning 70 on December 26, 2021. Happy birthday to my darling sister!

PAT The following is a reprint of an article I wrote, entitled, “How My Uncle, A Painter, Inspired My American Jewish Dream” which appeared in Reform Judaism.org on July 7, 2016.

I was 6 years old when my mother took my sister and me to our great Uncle Jennings’ studio by the ocean, where he drew a portrait of me. He said he saw something in my eyes that spoke of a deep soul. He died the next year, but I will never forget him.

Uncle Jennings was my Papa George’s brother, and I remember once asking my Nana Eva about him. She said he was “a Bohemian,” and the family didn’t really associate too much with him because they thought what he did was frivolous.

In my view, though, what Uncle Jennings did was anything but frivolous.

Jennings Tofel was born on October 18, 1891 in the town of Tomashev, in the province of Lodz, in central Poland. His father, Yosif Toflexicz was the town’s best ladies tailor. Jennings’ paternal grandfather, Reb Heshka, was the son of an eminent scholar, a dayan (judge of a rabbinic court) who, absorbed in his own scholarly pursuits, had neglected Heshka’s education. When Yehudah (Jennings’ Hebrew name) was born, his father imagined that his son would take up the mantel of a long family line of distinguished rabbis and men of learning.

But as a young boy of 7, Jennings had a terrible accident and broke his back. It was never set properly, and that fixed the course of his life – a life of pain and deformity. He moved to America when he was 14 years old, and in time, he entered college at the City College of New York. It was during that time that his artistic talent was recognized, and he started to paint. As a result, what originally appeared to be a curse was seen as a blessing, for the gift that emerged from his fingertips was truly extraordinary.

Jennings was an Expressionist painter. As Arthur Granick, a friend and avid collector of his works, once wrote,

“At one time Expressionism was considered, and often angrily dismissed, as ‘typically Teutonic’ or even ‘typically Jewish.’ But it is interesting to recall that the majority of immigrant artists either were full-fledged Expressionists or could, at least at some point in their career, be considered Expressionists.”

Jennings was influenced by the cry of anguish reflected in the works of Edvard Munch, a Norwegian artist of an earlier generation, who displayed the knowledge of the kinds of tortures invented by men for other men.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Jennings was a part of a group of talented men and women who formed an enclave within American art, a sort of equivalent to the Ecole Juive in Paris. These immigrants brought with them from the old country the Yiddish language, Jewish legend and lore, and art. Uncle Jennings was one of the best-known among this group of unknowns (the Whitney Museum of American Art purchased one of his pictures in 1932), and he became a protégé of American photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

Jennings’ essays “Form in Painting” and “Expression” for the Societe Anonyme were among the precursors to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and he also wrote numerous essays on art in Yiddish for Jewish publications; his written collections are now housed at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Today, his paintings are part of the Hirshhorn Collection, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, among others.

Uncle Jennings’ pictures are truly haunting. His figures are often distorted, like his own body. He used brilliant large swaths of color on the canvas. Many of his pictures portray biblical themes. When you see his paintings you never forget them.

Collection of Ali and Chris McCloud.

A portrait of that little 6-year-old girl sits in my home study. A soulful child, she was inspired by a strange little man to follow her dreams and express her passion and connection to her people. I look at it often and find that it, and the other paintings of Jennings Tofel that hang in my home, continue to inspire me and connect me to my own family’s history and the history of the American Jewish Diaspora. More than that, it reminds me constantly of the ongoing journey of that 6-year-old and her role in the journey of her people.

Rabbi Cantor Patricia Ernest Hickman is the spiritual leader of Temple Israel of Brevard in Melbourne, FL. She was ordained as a cantor by Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, and more recently received rabbinic ordination through the Rabbinical Academy, Mesifta Adath Wolkowisk. She is married to Ray Hickman and they are the parents of two grown daughters.

Additional Note: We credit most of our details about Jennings Tofel’s life to the incredible book, Jennings Tofel, published in 1976 by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York. We also acknowledge Anne Granick, Nina Abrams, Joan and Judy Reifler and the importance of word of mouth, legends and personal memories.